Written by Liv Donnadieu, J.D.

Cable television, sofas, personal kitchen, gaming consoles – sounds like a nice hotel room OR the royal in-custody treatment of jailhouse snitches. The unveiling of a rotten network of jailhouse snitches within Southern California has recently led to the adoption of State Bill “AB 359” limiting the benefits given to criminal informants to a $100 per case. How did we get there? And what to expect from AB 359?

Let’s find out!

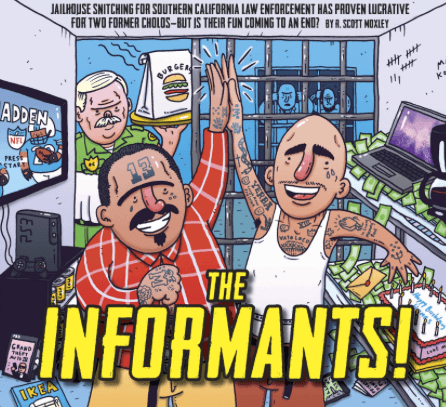

Meet two gentlemen, who despite being incarcerated, managed to collect hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash and services paid out by various Southern California law enforcement agencies in exchange for information that could help incriminate other inmates.

The Informants that Made it Rich

Raymond “Puppet” Cuevas and Jose “Bouncer” Paredes have recently agitated media across the country. And for good reason. Between 2011 and 2015, these two career criminals have become the two most lucratively paid jailhouse snitches. Records show that Southern California authorities have offered them over $335,000 in cash payments, leniency in their own criminal cases, and royal custody treatment such as housing cell with sofa, cable TV, gaming consoles, personal refrigerator and microwave, laptops, phone cards, out-of-custody family visitation rights, permission to cover surveillance cameras for privacy and so on.

Legality of Jailhouse Informants

The process of using jailhouse informants is actually a complex legal matter which has certain constitutional limits. Indeed, incriminating disclosures induced by jailhouse informants can only be admitted in court with respect to fundamental constitutional rights – right to counsel, right to a fair trial, right not to self-incriminate, etc.

In 1986, in Kuhlmann v. Wilson.[1], the U.S. Supreme Court considered that a defendant’s confession to an inmate informant could be admitted in court so long as the incriminating statement was spontaneous and unsolicited. Anything beyond mere listening steps can defeat the admissibility of a confession. Consequently, direct questions, inducements and other coercive methods leading to a confession are not be permissible.

Scandal

Records show that the treatment and compensation of Mexican Mafia members Cuevas and Parades went above and beyond that. Authorities would routinely send the men into jails to befriend suspects, and in cells wired with recording devices, Cuevas and Paredes would offer to help them avoid a death penalty from the Mexican Mafia, if they confessed a complete history of their alleged crimes.

This by itself would not be as concerning if not for the following fact. Prosecutors withheld from the judges and defense attorneys the illegal payments and leniency offered to the snitches in exchange for the information used to prosecute defendants in other cases.

California Halts Informant Payout with AB 359

As a result of these revelations, the Assembly Public Safety Committed has unanimously adopted an Assembly Bill “AB 359” limiting rewards given to criminal informants. The California Bill is now making its way to the state Legislature. Under AB 359, snitches like Cuevas and Parades will have their monetary and nonmonetary payments capped at $100 per case. Additionally, prosecutors would also be required to turn detailed informant histories over to defense attorneys no later than 30 days before preliminary hearings, including the substance of all communications with the informant, all consideration impliedly or expressly offered, and the informant’s complete criminal history.

By capping informant benefits along with better frame record keeping and disclosure requirements, AB 359 is expected to lead to certain changes. There will be a reduction in the amount of wrongful convictions. It will give defendants a fair trial and a level playing field. And most importantly, it will preserve the integrity of our justice system.

[1] Kuhlmann v. Wilson, 477 U.S. 436 (1986).

Disclaimer: This article has been prepared and published for informational purposes only and is not offered, nor should be construed, as legal advice.